You may have heard that the suicide rate increases during the winter months due to seasonal affective disorder (the winter blues) or that it specifically increases during the holiday season. People are quick to invent explanations for this correlation, most commonly that the holidays exacerbate social isolation, loneliness, and economic or other struggles. No such explanations are necessary, however, because the correlation between suicide and holidays is a complete myth.

In fact, according to the CDC, for many years December has had the lowest rate of suicide in the US, followed by November and January. So if anything there is a protective effect of the winter and/or the holidays, or it may just be that there are factors present in other seasons that increase the risk.

It is important for the media to get this detail correct because it is possible for irresponsible reporting to actually increase the public risk of suicide. There is a phenomenon known as “suicide contagion” in which reporting on suicide can have a negative effect on vulnerable individuals, increasing their risk, which can in turn increase reporting in a positive feedback loop. To mitigate this effect there are published journalistic standards on how to report about suicide. One of those standards involves not hyping “epidemics” of suicide – especially when they are not actually true.

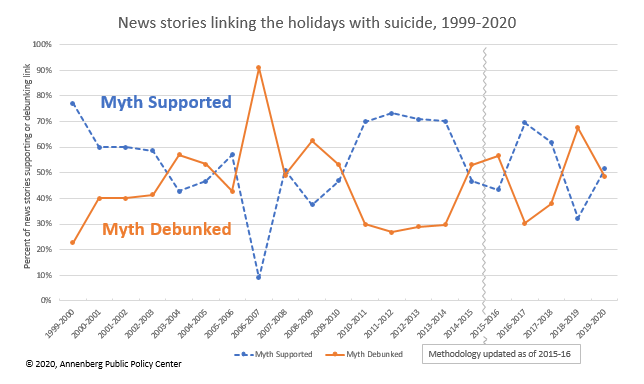

For the last 21 years the Annenberg Public Policy Center has been tracking reporting about the holiday suicide myth. They found that in most years there is more reporting spreading the myth than debunking it, and in only 3 of the last 21 years did 60% or more of the reporting they found debunk the myth. Interestingly, in the 2006-2007 season 90% of reporting debunked the myth, presumably due to efforts to spread reliable information. But this peak effect lasted only a year, with a majority of reporting supporting the myth again by 2009. The myth (like most such myths) has proven remarkably persistent.

Regarding the COVID-19 pandemic there is legitimate concern that this will have the effect of increasing suicides by increasing suicide risk factors. These risk factors include anxiety, depression, isolation, and economic and other stressors. We also have data from prior pandemics and epidemics that do show a tendency to increase suicide rates.

For this reason it is prudent to increase awareness of the risk of suicide, warning signs, and resources available for those at risk. These preventive measures are always a good idea, but may need to be increased as the pandemic drags on. As noted above, however, it is equally important the journalist understand how to responsibly report about these concerns, and to not exaggerate them or present them in hyperbolic terms, but rather to direct readers to helpful resources. Further, don’t fall for the “Holiday COVID” narrative, because it is simply not true.

There remains, however, the scientific question of whether or not the COVID-19 pandemic has, in fact, increased suicide rates in any locations or demographics. There is always a delay in collecting and analyzing data, so we don’t have real-time information. At present we have published data looking mostly at the Spring shutdown period. During this period there was no apparent increase in suicides, or even a decrease, at least in industrialized nations. This was shown by multiple studies. In fact, Japan saw a statistically significant decrease in suicide in the Spring by 12% (with a corresponding increase of 13% over the Summer). Other countries so far have not shown a similar Summer increase during the second wave of the pandemic.

We also need to note that data from poor and developing countries is mostly lacking, and so these conclusions cannot be extrapolated beyond the more wealthy nations where data is available.

The bottom line is that it is too early to tell what the overall effect of the pandemic is on suicide rates. The shutdown itself did not increase suicide rates. This may have been due to a “honeymoon effect” as people pulled together to deal with the pandemic, and also as people were helped by government subsidies.

As the pandemic drags on, however, there is legitimate reason for concern because suicide risk factors are increasing due to the impact of the pandemic. However, it may be possible to mitigate this risk through adequate economic aid to those most affected by the pandemic, to increased surveillance of warning signs and availability of suicide prevention resources, and through responsible reporting (following published guidelines).

Overall we need to be careful not to get ahead of the data, and not to create a pandemic-suicide myth similar to the holiday-suicide myth. Once created, myth monsters are almost impossible to slay.